Sam Keen, a pop psychologist and philosopher whose best-selling book “Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man” urged men to get in touch with their primal masculinity and became a touchstone of the so-called men’s movement of the 1990s, died on March 19 in Oahu, Hawaii. He was 93.

His death, while on vacation, was confirmed by his wife, Patricia de Jong. The couple lived on a 60-acre ranch in Sonoma, Calif.

Mr. Keen, who described himself as having been “overeducated at Harvard and Princeton,” fled academia in the 1960s for California, where he led self-help workshops and wrote more than a dozen books. He became a well-known figure in the human potential movement of that era.

In the 1970s, he delivered lectures around the country with the mythology scholar Joseph Campbell. He also gave workshops at two of the wellsprings of the New Age: Esalen Institute in Big Sur, Calif., and Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, N.Y. Mr. Keen’s specialty was helping middle-class seekers slough off the expectations of family and society, and discover what he called their “personal mythology.”

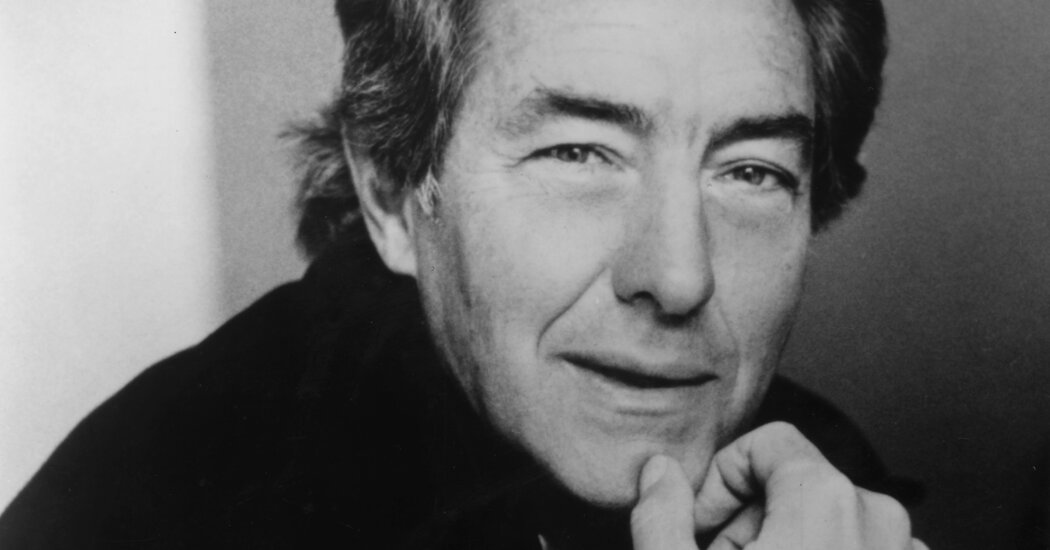

A long conversation that the ruggedly handsome Mr. Keen had with the journalist Bill Moyers, broadcast on PBS in 1991, brought him national exposure the month that “Fire in the Belly” was published. The book spent 29 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.

Mr. Keen told Mr. Moyers that he had spent much of his early life trying to meet expectations about masculinity, especially those placed on him by women.

“They were the audience before whom I dramatized my life,” he said, “and their applause and their approval was crucial for my sense of manhood.”

In “Fire in the Belly,” which was partly inspired by a men’s discussion group he belonged to, Mr. Keen argued that men must discover a new kind of manhood apart from the company of women.

“Only men understand the secret fears that go with the territory of masculinity,” he wrote.

“Fire in the Belly” and an earlier, bigger best seller, “Iron John” (1990) by the poet Robert Bly, became the twin handbooks of the men’s movement, a psychological response to the gains made by feminism.

The movement’s principal authors and workshop leaders claimed that modern men had become “feminized” by demands that they get in touch with their feelings, seek consensus rather than lead, and become domesticated rather than follow their warrior spirit.

At woodsy retreats, men beat on drums, screamed primally and broke down in tears, grieving injuries that had been done to them by society, and especially by absent fathers.

The movement was an easy target for parody, which came from many cultural quarters. But books like Mr. Bly’s and Mr. Keen’s attracted large readerships, both male and female. In 1992, the year after the wrenching Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas, which alerted many Americans to the issue of workplace sexual harassment, Mr. Keen was invited to lead a private seminar on gender dynamics for senators in Washington.

The men’s movement of the 1990s might have sowed some early seeds of what became the current “manosphere,” the world of misogynistic influencers who celebrate harassment and violence toward women. But Mr. Keen himself was not a misogynist, and he embraced feminism. He applauded its analysis of a patriarchal society that wounded both women and men, and he wrote that women’s liberation was “a model for the changes men are beginning to experience.”

From the men’s movement, Mr. Keen went on to become a guru of the flying trapeze, encouraging men and women to overcome their psychological fears by learning to swing from a circus bar 25 feet off the ground.

He set up a trapeze on his property in the foothills of Sonoma County and wrote “Learning to Fly: Trapeze — Reflections on Fear, Trust, and the Joy of Letting Go” (1999).

Alex Witchel, a Times reporter who visited him and took him up on the challenge, noted that Mr. Keen, then 67, wore tights and slippers and “looked like a bony old bird, his frame lean and spare from years of flying.”

Samuel McMurray Keen was born on Nov. 23, 1931, in Scranton, Pa., the second-oldest of five children of J. Alvin Keen, the director of a Methodist church choir, and Ruth (McMurray) Keen, a teacher. His early years were spent in Maryville, in East Tennessee.

When Sam was 11, his family moved to Wilmington, Del., where his parents ran a mail-order business selling uniforms to military nurses.

He graduated from Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pa., outside Philadelphia, and then earned a Doctor of Theology degree from Harvard Divinity School and a Ph.D. in philosophy of religion from Princeton University.

In 1968, on a sabbatical from the Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Kentucky, he visited the West Coast and became, as he once told an interviewer, “engulfed in the California madness.” He never returned to academia.

He became a freelance journalist, writing for Psychology Today and other magazines and interviewing some of the leading lights of New Age spirituality, including Carlos Castaneda, Chogyam Trungpa and Mr. Campbell, whose “The Hero With a Thousand Faces” inspired both the Grateful Dead and “Star Wars.”

His early book “To a Dancing God” (1970) described his rejection of the conservative Christianity in which he was raised and his embrace of direct spiritual experience.

A later book, “Faces of the Enemy” (1986), a study of the use of propaganda to prepare citizens for war, was made into a PBS documentary.

Mr. Keen’s marriage to Heather Barnes ended in divorce after 17 years. A second marriage, to Janine Lovett, also ended in divorce. Besides Ms. de Jong, whom he married in 2004, he is survived by a son, Gifford Keen, and a daughter, Lael Keen, from his first marriage; a daughter, Jessamyn Griffin, from his second marriage; six grandchildren; and three siblings, Lawrence Keen, Ruth Ann Keen and Edith Livesay.

Mr. Keen’s emergence as a spokesman for the men’s movement was somewhat accidental. He had been leading various types of workshops when his publisher, sniffing something in the air, asked him to write about modern manhood.

As “Fire in the Belly” caught fire with readers, Mr. Keen was disdainful of some of the more easily lampooned aspects of the movement.

“I wouldn’t be caught dead with a drum,” he said.